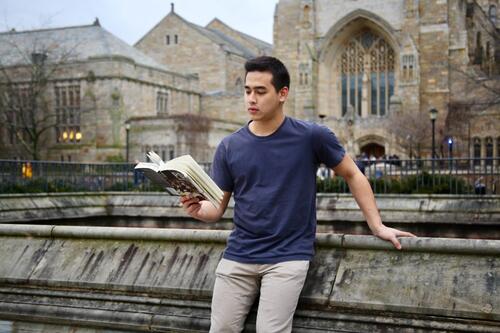

As he talks, one of Pirawat “Putt” Punyagupta’s legs tends to keep a rapid tempo, jumping up and down with the same speed that his hands move right to left, up and down, in aerial curlicues and waves that meld with his thoughts. It’s not that he’s nervous, or that he’s excited (though I’m hoping he isn’t bored). It’s that he’s moving through ideas faster than most people can come up with them.

Putt is the only South Asian Studies major in the class of 2023, a degree he’s paired with a primary major in History. His interests span 11th century Buddhist manuscripts, 20th century political theory, and a host of Persian, Thai, and Indian dishes he cooks par excellence. When we spoke, he had just returned from a trip to Bangladesh, where he visited the Bangla Academy, conducted outreach on behalf of an old employer, and educated his Instagram followers about modern Bangladeshi history. In every respect, he’s one of the most remarkable people—and engaging conversationalists—you can run into on campus. That’s partially because the odds are good that whatever your mother tongue is, he can probably speak it. English (native), Thai (native), Mandarin (fluent), Farsi (fluent), Hindi, Urdu, Sanskrit, Pali, Tamil, Bangla, and barely some Russian, he tells me, as if proficiency in 11 languages is almost an afterthought.

Putt grew up in Thailand, the son of an American mother and a Thai father. As a child he cultivated an interest in politics, cooking, and history. When we spoke, he smiled as he mentioned doing “typical” speech and debate and Model UN things in high school, where he also took several years of Mandarin and picked up Farsi from informal tutoring by a family friend. Until that point, he told me, he didn’t think of himself as a language person. But the serendipity of starting Mandarin has translated into years of language courses, two Critical Language Scholarships (in Farsi and in Hindi), and a rich vein of research into the politics of pluralism.

When Putt matriculated to Yale in 2018, he enrolled in the Directed Studies program, which offers a group of first-years an intense interdisciplinary introduction to the seminal texts of Western and Near Eastern thought. The other course he took his first-year fall was Elementary Sanskrit, a choice he was inspired to make by his interest in its significance for historical linguistics and in awareness of Yale’s role in pioneering the study of Sanskrit in the Western world (Yale was the first American university to endow a professorship for Sanskrit, in 1841). For the next two semesters, though, he continued to work on his Mandarin.

He told me, “Chinese was my primary focus until the pandemic. Before the pandemic I thought I would be an East Asian Languages and Literature major in addition to History. But in the spring semester [of my gap year] I audited L2 Sanskrit with Professor Uskokov and that allowed me to pick back up where I left off. I progressed to a point where I was able to read basic texts and poetry and that got me much more interested. The first semester’s so much rote memorization, and it’s the only way you can really learn the language. So it can be monotonous, but it’s highly rewarding.” Putt pursued his Sanskrit studies the summer after his gap semester at the South

Asian Summer Language Institute at UW-Madison. By the time he finished the institute, he had gone from L1 Sanskrit to L5 in a few months, and he’s taken L5 Sanskrit courses every semester since. He’s spent other summers studying Farsi on Zoom, learning Hindi in Jaipur, working at a law firm in Taiwan, researching the Mekong River watershed with the Stimson Center, and supporting a Thai archival learned society, the Siam Society.

Putt groups his South Asia-related courses into three categories: courses on pre-modern comparative religion, which includes Sanskrit classes; contemporary South Asian history; and security and international relations. But he emphasizes that each category is not discrete: they exist in conversation with each other, promoting an understanding that is mutually beneficial. All, he says, relate to pluralism and the question of how a nation-state facilitates conditions in which multiethnic polities can coexist, a question he sees as logically suited to South Asia. In particular, he told me, “One thing I hope to explore in the future is the notion of cultural property and contested religious places in South Asia and the implications for pluralism more broadly. Languages have helped me understand that better.”

The interdisciplinarity of Putt’s interests can be glimpsed in his two theses. To complete the requirements of the History major, he’s writing about “the linguistic reorganization of Indian states, specifically within the context of South India and the Madras Presidency.” The Madras Presidency, a British Raj-era administrative division, included all or parts of the current Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, and Odisha. All of those states were constituted in 1956 and afterwards on linguistic lines. Putt’s work thinks about the impacts of what he describes as “monocultural bounds” imposed on a region that has historically been “polyglossic.” “I did my archival research on how this process affected Tamil people on the other side of the Bay of Bengal in Malaysia and Singapore. For a long time these were parts of the same empire and there were many networks connecting these two places. How did the creation of this cultural homeland affect networks of Tamils elsewhere, and how did they respond to the changes that were happening there?” Working with Indian government documents and Tamil newspapers sourced from the Library of Congress, he found that what is often read as a domestic event had reverberations over a wide area and array of networks. He said, “the reorganization emboldened many linguistic nationalists. When the people migrating between the two communities had problems [Tamil Nadu] would petition the Indian government on behalf of these communities.” In a way, he says, a relationship centered on cultural patronage emerged that can provide a key lens onto the nature of the post-imperial state.

Putt’s second thesis, for South Asian Studies, goes in a very different direction. Working with the philosopher Vedanta Desika’s 14th century soteriological drama Sankalpa Suryodayam, which instructs its readers on how to gain moksha (liberation) in the context of the Vaishnava sect of Hinduism, he’s developed an argument that compares Sankalpa Suryodayam with another one of Vedanta Desika’s works and analyzes how the sage portrays the preconditions for liberation in both works for the different audiences he tries to speak to. Encouraged by Aleksandar Uskokov, Lector in Sanskrit, and David Shulman, an Indologist at Hebrew University, Putt has incorporated Tamil into his thesis. The works he analyzes are written in Manipravalam, a literary register that combines Sanskrit and Tamil, and he chose to declare the major in South Asian Studies at the beginning of his senior year with the thesis concept already in mind.

When he graduates from Yale, Putt will turn in the direction of the third bucket of his interests: international relations. At the end of 2022 he was named as one of 143 Schwarzman Scholars selected from universities around the globe. The scholarship is for a one-year, fully-funded master’s degree from Tsinghua University in Beijing. Explaining his interest in the program, Putt explained that he has never visited Mainland China despite studying Mandarin for a decade and emphasized his plans to study the relationship between China and Southeast Asia during his time in Beijing. After graduating from the program, he plans to work for some time before heading to graduate school, where he’ll likely study law or history.

When I asked him about his choice to study South Asian Studies, which is uncommon among undergraduates, Putt explained that he felt that “the interdisciplinary aspect of the major has been good in facilitating a wide range of interests for me that pertain to the region. Sometimes interdisciplinary can feel a bit too messy, but the major has allowed me to design a very comprehensive curriculum for myself that I’ve been really happy about.”

In addition to his academic interests, Putt serves as President of the Yale Russian Chorus, works as a Writing Tutor at the Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, and cooks a mean fesenjan, a Persian dish of pomegranate chicken. As we finish our conversation and move into talking about our shared class on the Indo-Islamic tradition, taught by Professor Supriya Gandhi, I mention that I’d love to try some of his Thai dishes. Putt, for once, looks a little sheepish. “The funny thing is, I can’t really make any of those without recipes.” Proof, I suppose, that nobody’s perfect.

Byline: Daevan Mangalmurti