NEW DELHI: India is in the midst of its parliamentary elections, among the biggest democratic exercises anywhere in the world. Narendra Modi, the incumbent prime minister, seeks a second term in office. The economy is strong, but the pace of growth is slowing and the unemployment rate is at 6.1 percent. He remains popular, and he has made the elections a referendum on his handling of national security against the backdrop of Indian airstrikes on Pakistani territory – retaliation for a February terrorist attack on Indian security forces in Kashmir. Among his selling points is the view that he is tough on corruption. The opposition, especially the Congress Party, has tried to attack him on that count by focusing on alleged corruption in a recent defense deal. There is little evidence so far that Congress Party has convinced the electorate, but this political contestation underscores the persistent challenges India faces as it pursues defense modernization.

Ironically, the controversy over military modernization rages while aging aircrafts fall from the sky and accidents damage naval modernization. Space technology is one part of Indian defense that seems to register steady progress. Meanwhile India’s rival neighbors continue modernizing their capability to threaten India.

Political squabbling bedevils India’s plans to replace its fleet of aging combat aircraft. The French Dassault Rafale has a troubled procurement history, and the controversy has influenced politics un the run-up to the general elections with accusations of corruption and impropriety. A spotlight is on India’s troubled capability-development efforts and stagnating reforms initiated to streamline procurement and create indigenous defense production capacities.

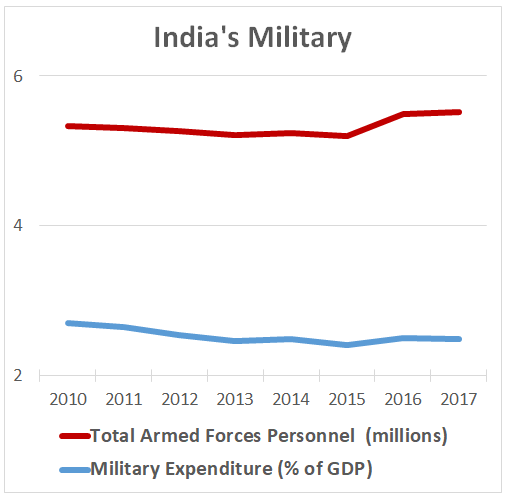

Voters will scrutinize spending priorities with India poised to become the world’s most populous nation. Yet the nation ranks fifth for military spending, suggests a report from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Among the controversial decisions of the Modi government was the purchase of 36 ready-to fly planes rather than 126 fighter jets with a technology-transfer clause built in, as had been previously desired. The Indian Air Force contest for 126 Medium Multi Role Combat Aircraft was announced in a request for proposals issued in 2007. In 2011, IAF eliminated four proposals, leaving the Rafale and the Eurofighter in contention. In 2012, when the opposition Congress Party was in power, the government declared a bid by Dassault as the lowest bid. However, successive governments did not place an order, with escalating price tags and hesitation about a work-share requirement with state-controlled Hindustan Aeronautics Limited. In 2015, the Modi government opted to buy 36 Rafale aircraft directly through a government-to-government contract, citing “critical operational necessity” and the need to cut time and costs.

Personnel vs. technology: India’s defense budget as a percentage of GDP has dipped in recent years while funding devoted to salaries and pensions rises (Sources: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute; International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance; World Bank)

Personnel vs. technology: India’s defense budget as a percentage of GDP has dipped in recent years while funding devoted to salaries and pensions rises (Sources: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute; International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance; World Bank)

While the acquisition of 36 Rafale for the IAF is by no means the worst solution to India’s fighter aircraft problem, the delay in the procurement of an adequate number of replacement combat aircraft has left the IAF with a capability gap. The piecemeal acquisition of 36 aircraft, and possibly another similar performing aircraft like the F-16 or the Gripen, will hamper fleet standardization and do little to ameliorate its force structure predicaments – a result of its declining number of fighter squadrons for confronting growing air threats posed by China and Pakistan. The Pakistani Air Force has the US-made F-16. Meanwhile, the IAF will continue to be hard-pressed to deliver on traditional operational roles like air defense, close air support and strike capabilities.

India’s defense modernization efforts ultimately depend on reforming and building an efficient procurement and indigenous production capability. One of the fundamental issues relate to funding allocated for national security, and the share of those funds for defense modernization or capital expenditure. The defense budget in recent years has fallen to about 1.5 percent of India’s GDP, with an increasing component of funding allocated towards salaries, pensions and other operating expenses. Personnel costs are crowding out resources for equipment, with India’s standing army among the world’s largest, second only to China’s. The shrinking amount for capital expenditure leaves the army, navy and air force falling short in modernization goals with implications for India’s defense posture.

The BJP-led government since 2014 has initiated reforms to help streamline the procurement process and create indigenous defense development and production capacities under its “Make in India” initiative, yet these have done little to reverse or arrest the decline.

One of these policies – for “strategic partners” in building major weapons platforms for the military under the defense procurement policy – continues to receive pushback from the private sector. The policy grapples over issues such as whether the model allows one foreign company in one segment to ally with Indian companies in multiple segments such as ammunitions, aircraft, warship, target acquisition and other critical material. Questions also emerge over how to ensure competitiveness after choosing a private-sector firm as a strategic partner. A much-criticized recent example: selection of a newly formed company as Indian partner for the Rafale. The capability of nominated private Indian firms to demand or absorb a greater share in manufacturing or technology are at a nascent stage and might inadvertently go against the purpose of the Make in India campaign.

So far, no major defense contract has gone to the private sector, barring the ₹4500 crore deal to supply specific artillery systems that went to Larsen & Toubro, worth about US$700 million, and this reflects a lack of policy execution by the government during the past five years. In other words, continued reliance on foreign manufacturers hinders development of an indigenously focused defense industrial base. India’s attempt to develop and build a light combat aircraft named Tejas has yet to translate into any tangible operational capability after more than 30 years in the making. The aircraft continues to face developmental and quality issues with state-run Hindustan Aeronautics Limited failing to meet modest delivery schedules consistently of eight aircraft a year. The Ministry of Defence’s inability to produce guidelines that streamline its acquisition process has led to more government negotiations, with the hope that the procurement cycle becomes less cumbersome and less controversial.

There exists an urgent necessity to reconcile such structural dilemmas of the procurement process, including declining capital investment relative to personnel costs. Previous instances of major defense reforms occurred only after conflict – the 1962 defeat by China and the shock of Pakistan’s 1999 Kargil incursion. The request for proposals and the requirement for 126 combat aircraft and the piecemeal acquisition of 36 Rafales must be taken as a test case. Lessons must be learned to improve the defense procurement process without the nation getting bogged down in controversy over corruption involving high-value acquisition.

Modi was elected in 2014 with a substantive electoral mandate on the promise of a corruption-free government, yet finds it so difficult to move ahead with the procurement of 30 odd fighter jets. This is a reflection of India’s convoluted management of defense policy. And it is not readily evident that a new government, if one were to come to office in May, could navigate these choppy waters more effectively.

Harsh V Pant is director of Studies at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi and professor of international relations at King’s College London. Pushan Das is an associate fellow and program coordinator with Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.