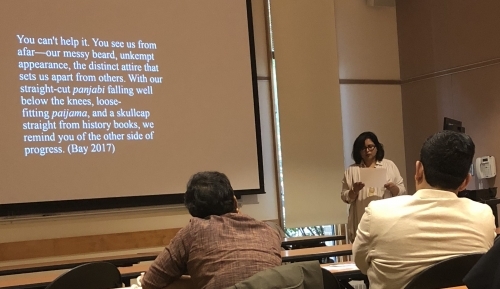

The South Asian Studies Council at the MacMillan Center invited Nusrat Chowdhury, Professor of Anthropology at Amherst College, to speak about her paper, “The Ethics of the Digital: Crowds and Popular Justice in Bangladesh,” on September 20, as the inaugural talk of its Fall Colloquium Series.

Professor Chowdhury kicked off the event with a surprising request: that each of the twenty-five or so participants in the room introduce themselves to the rest of the group. The participants were diverse in age and field of expertise—some were professors of Southeast Asia Studies or undergraduate students pursuing an English degree, while others were English professors or residents of the New Haven area. Yet, despite their differences, all the participants possessed a shared passion that brought them to the event that day.

An expert on everyday politics, Professor Chowdhury drew our attention to the politics behind public gatherings in an investigation of gender, religion, violence, and terrorism. She first pointed to the student-led Bangladesh road-safety protests and the arrests of activists that followed as examples of government crackdown on online and street activism. Bangladesh’s Vision 2021, a political vision of the Bangladesh Awami League, is paradoxically illustrative of the technological optimism the government holds and the government’s desire to control digital spaces.

Professor Chowdhury next examined the contradictory nature of crowds. In one segment of surveillance footage, we saw a crowd of men collectively surround and publicly humiliate two women. “Men have certain power in public spaces” Professor Chowdhury states. “In Southeastern culture, crowds are gendered male, while the individual is gendered female.” Moreover, Professor Chowdhury pointed to another situation in which a video of a young boy being beaten and lynched by a group of men made waves across the internet. “Violence against poor people and kids is not uncommon,” she states. “And they are often conducted by people of the same class.”

In both the above examples, it was clear that the crowd existed for insidious purposes. However, this notion was complicated by the fact that members of the guilty parties were identified and tracked down by internet vigilantes, as part of the powerful “digital crowd.” Without a digital audience, violence against women, children, and the poor would not have the visibility they do today. Thus, “crowds are implicit in crimes,” Professor Chowdhury stated, “but also exonerated,” depending on whether they are “Responsible Citizens” or “Criminal Crowds.”

To conclude, Professor Chowdhury left us with some food for thought. “Emotions spread like viruses across the internet,” she stated. “The digital exists in part because we take voyeuristic pleasure in scenes of crowd and public violence.” While gatherings are fueled by violence, they also serve as a means for justice and empowerment of the masses—a reminder that we, as individuals, hold immense power and responsibility.

Written by Sophia Zhao.