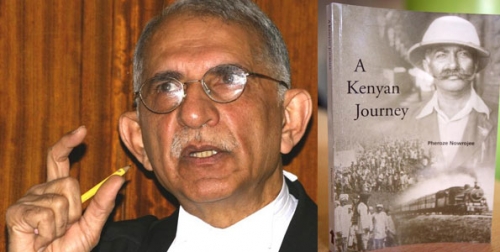

Pheroze Nowrojee LLM ’74, the renowned human rights lawyer and author, gave the South Asian Studies Council’s Annual Gandhi Lecture on October 2, M. K. Gandhi’s birthday, in Henry R. Luce Hall Auditorium at the MacMillan Center. (view video) Senior counsel and advocate in the High Courts of Kenya, Tanzania, and Zanzibar, Nowrojee was awarded the International Bar Association’s Bernard Simons Memorial Award for the Advancement of Human Rights, among many other honors, in a distinguished career. “It is a pleasure to be back,” he said on his return to Yale.

Nowrojee’s talk, ‘Gandhi and Kenya, 1919-1929: An Unlikely Theatre of Operations?’, highlighted “a pivotal time in Gandhi’s life.” It was a time, Nowrojee said, “when Gandhi transformed from a diasporic hero to an Indian hero.” Till now the Kenyan connection has remained underappreciated. Nowrojee’s lecture, drawn from a book on Gandhi and East African politics that he is now completing, illuminated this connection with remarkable breadth and nuance.

“Kenya was an unlikely field for this transformation,” Nowrojee continued. In the early twentieth century, Indians in Kenya faced similar problems as those Gandhi had personally encountered in South Africa. Indians were caught between the condescension of white settlers and the distrust of black African natives, leading to a variety of exclusions and humiliations. In the unequal treatment of Indians in Kenya, Gandhi found a political opportunity. He began campaigning for the equal treatment of Indians as subjects of the British Empire in all British territories, which he hoped would tackle the problem of the ‘color bar’ and restore ‘national respect’ to Indians outside India.

“Swaraj with the Empire,” Nowrojee argued, “that is, the equal treatment of Indians in British territories outside India became Gandhi’s priority at this time.” With a coupling of immigration rights within the Empire and respect, Indians as a people could be confident of their status within the imperial hierarchy. “If Indians in a British colony in Africa won equal treatment, then the equal treatment of Indians would be secured throughout the Empire,” Nowrojee maintained.

A crucial subject brought to light by Nowrojee’s lecture was the role played by the Working Committee of the Indian National Congress in the East African campaigns. “Kenya was not only of relevance but qualified for the Congress’s intervention,” Nowrojee reminded the audience. C. F. Andrews, a British missionary and close collaborator of Gandhi and the Congress, went to Kenya to investigate the conditions of Indians there in 1919. He conducted dozens of interviews and wrote a book on Indians in Kenya in 1920. Nowrojee quoted from one of Andrews’s missives where he said, “The question of equal treatment of Indians would be settled in the colonies.”

The international significance of Gandhi’s intervention in Kenya was not lost either on the white settlers there or on the imperial government in Britain. The perceived rights of the Dominions, i.e. white-settler territories of the British Empire, of excluding Indians had been transformed from an abstract matter to a fiery political question. Gandhi had used Andrews’s fieldwork in Kenya to particularly good effect with articles in Young India, a weekly he published at the time, and by communicating with persons of influence in Britain. Thus, any decision taken in Kenya would show the way for other Dominions.

In this context, Nowrojee argued, the Removal of Undesirable Persons ordinance and particularly the Devonshire Declaration of 1923 assumed especial significance. The Devonshire White Paper, as the Declaration was also known, issued by the British Colonial Secretary Lord Devonshire (Victor Cavendish), affirmed Kenya as an African territory and that in any circumstances where African and immigrant interests were in conflict, the native African interests should prevail. The White Paper advanced a model of trusteeship where the British government in London was seen as the trustee of the Kenyan people and thus responsible for their well-being over other immigrant communities, including white Europeans.

“The Devonshire Declaration marked a sea change in the history of the Indian independence movement,” Nowrojee observed. It was clear to Gandhi that the White Paper was meant to stem the tide of calls for equal treatment of Indians. “The decision was seen not merely as one on Indians in Kenya but on Indians across the Empire,” Nowrojee told us. The Indian National Congress held a special session in Delhi in 1923 to discuss the Kenya issue, where C. Rajagopalachari would go on to say that Kenya represented a particular challenge, “the challenge of making ourselves free.”

In closing his lecture, Nowrojee spoke of how Gandhi never stopped exposing the imperial excesses in Kenya by continuing to publish more articles in his outlets. The equal treatment movement had in fact denied self-rule to white settlers in Africa and delayed the union of white Africa. For Nowrojee, “this was the biggest political achievement by Indians prior to Independence.” And the Devonshire Declaration reoriented Indian efforts toward national independence rather than equality within an imperial fold.

In time, the influence of the Indian independence movement and Independence itself would be catalytic for Kenya and all of Africa through the 1960s. Nowrojee related a moving account of a motorcade which took a small part of Gandhi’s ashes, after his assassination in 1948, to be immersed at the source of the Nile, a story that surprised almost everyone in the audience. That, indeed, is Nowrojee’s rare gift: to renew our ideas of the familiar and to broaden the scope of the connections between peoples across two continents.

The South Asian Studies Annual Gandhi Lecture is sponsored by The Bhatt Family Fund.

Written by Anurag Sinha, a Yale graduate student in the department of political science.